EXIT-Spielräume – Wirkkraft des Ungewissen

Have you ever been trapped in a story? Equipped with logic, curiosity and playfulness, each creature in the respective room can creatively unfold together on an adventurous journey of escape. The special part about the so-called Escape Rooms (EXIT) is that the players are locked in a room for a certain period of time and have to independently explore the rooms and work out solutions to be able to leave them again later.

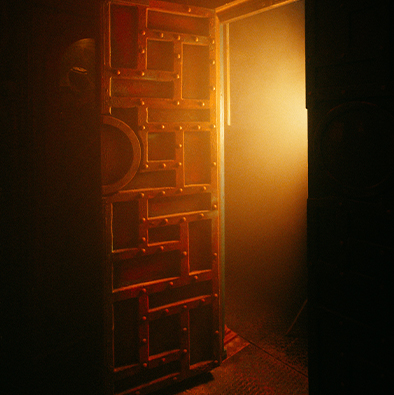

Behind each object, a crucial clue could open the way to the next room – a shifted perspective.

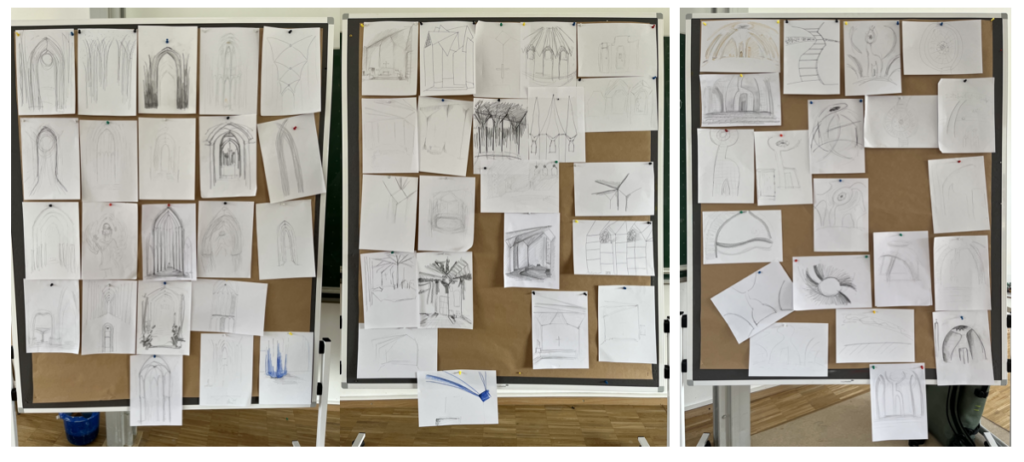

A shifted perspective – a new door – all in all: a partially mobile interior architecture. With great attention to detail, an ambience is created that transports all players into a story that can only be understood interactively through the cooperation of all and can therefore be told together. Every arrangement in the room ensures or blocks the possibility of progressing to the next room. Do the players allow themselves to (still) uncertain playing spaces with conscientiousness – feel them out and think them through, then they experience a very conscious steering. The moment when they realize that the experience of the path lies in their own hands…

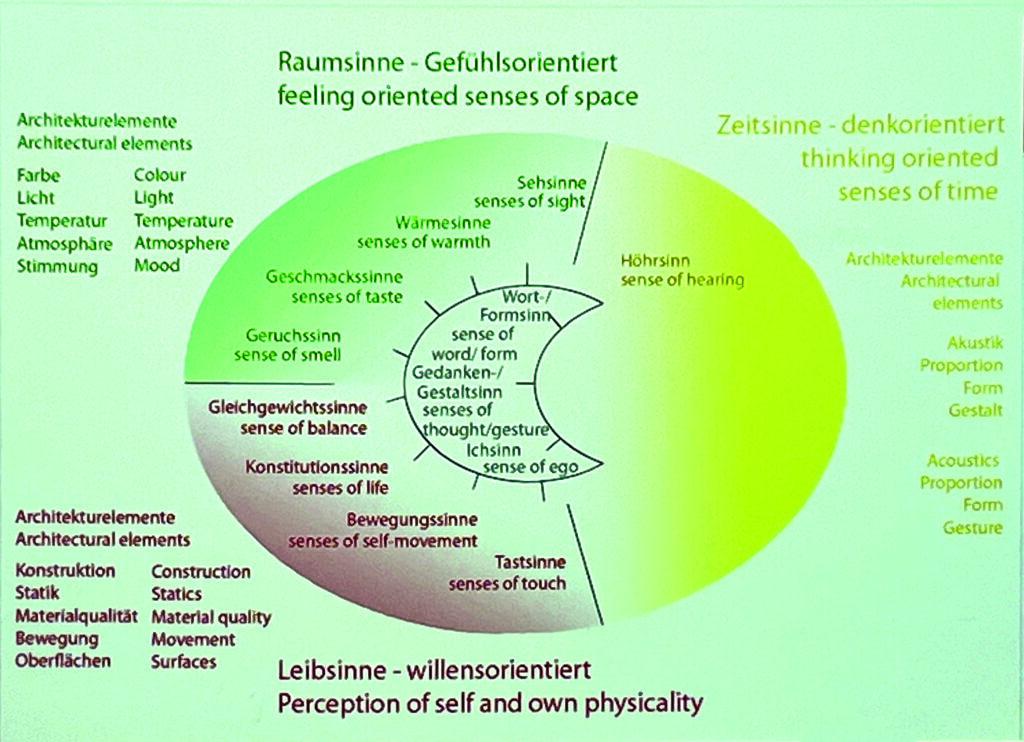

My assumption that this type of spatial encounter is linked to very specific forms of interior architecture and stimuli will be examined in the further observations.

If we look at the appeal of the unknown, it quickly becomes clear why EXIT spaces make so many happy: We are faced with something completely diffuse without certainty of knowledge and can practise awakening in this blind state in a new way. Recognizing ourselves as an active co-creator of the space, even when simply rearranging objects, can be liberating and fulfilling. The aesthetics of the unknown lie in this freely designable space and the actual discovery of the new, the teasing balancing act between loss of control – due to the unfamiliarity of the situation – and the possibility of control due to one’s own choice.

On the other hand, experiencing the stimulus of „being included“ can both motivate and invite you to go on your own creative mental journey, enriching you, but also stressing you.

In this resulting „living“ space, the surprise factor is sometimes so great that the mastered interior design with the supportive acoustics of the rooms, can leave people amazed and they discover how versatile some objects actually are.

By perceiving the dynamic interior architecture, the whole room becomes much more organic and flexible than it would be from a structural-spatial point of view. Especially here, the experience of teamwork and interaction is particularly great. Only together it´s possible to recognize the riddles and the use of some items. Anyone who has already tried something „unsuccessfully“ will soon be joined by someone else with another idea and can benefit at a later point in time from the previous experience and the knowledge gained from it. The spatial experience is therefore „moved“ in exactly the same way as the respective players. This makes it possible to leave everyday life to enter into a completely new situation that requires full attention and concentration – active relaxation with a touch of adrenaline.

Fascinated by the idea and aesthetics of the unknown and its power, I wanted to find out more about the so-called Escape Rooms and was delighted that the founder of EXIT in Berlin-Mitte (Friedrichstraße 101) Max Mühlbach agreed to answer a few questions about the creation and special features of these rooms.

A big thank you at this point for his openness!

Jonna Louise Besuglow:

„How long does it take – from the planning drafts to the structural implementation – until an

EXIT Escape Room is completed and ready for use?“

Max Mühlbach:

„That varies greatly. There are game designers/room designers who build turn-key games in 2-3 weeks and others plan and build games in 2 years. Our approach lies in the middle ground:

Game design and story are created in about 4-6 weeks, every now and then we use a kind of board game, on which we test the process. The pre-construction takes 2-4 months and the installation is then quite quick. Depending on how well it was planned, you have to go through another phase of 4-6 weeks for testing and optimization, sometimes even during live operation.“

Jonna Louise Besuglow:

„How important is the daily use of the rooms?“

Max Mühlbach:

„It’s negligible. The room is like a computer that has to be switched on before use and

shut down afterwards. Every now and then it needs an update, otherwise it runs if nobody breaks anything.“

Jonna Louise Besuglow:

„What characterizes the interior design of the individual EXIT rooms?“

Max Mühlbach:

„They are all multi-room games, so no world is smaller than 3 rooms and we strive for a very immersive setting.“

Jonna Louise Besuglow:

„What’s so special about the magnetic mechanism that closes and opens doors and drawers?“

Max Mühlbach:

„It’s relatively little magic. The e-magnets are supplied with electricity and therefore hold together; as soon as the power is switched off, the door or drawer can be opened. Sometimes we reinforce the effect with springs or sound.“

Jonna Louise Besuglow:

„How do you experience the changing behavior of the players based on the space?“

Max Mühlbach:

„It’s huge fun. At the beginning, nobody knows what to do with themselves, there are no

rules, so you usually need some time to get into the room. Over time you get into a flow, but every group here is individual. Observing that and guiding the players on the right path is a great task.“

The interview with Max Mühlbach makes it clear that the effectiveness of the EXIT Rooms is primarily due to the interior design, in this case the detailed multi-room design and the selected sound and lighting effects.

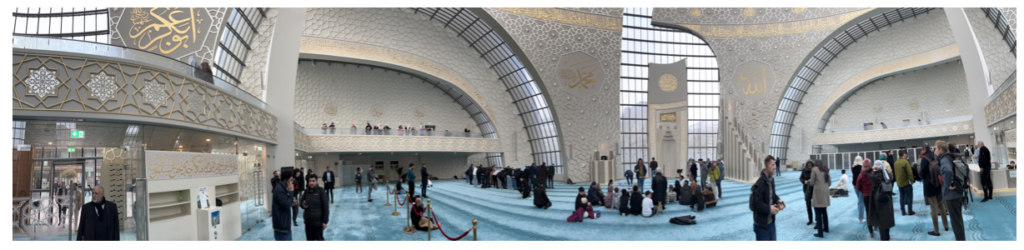

As an observer I have long noticed, even outside of EXIT play spaces, that the behavior of those present in the room changes depending on the room. This often underestimated spatial effect led me in June 2024 to interview around 50 participants in the EXIT Escape Room at the Admiralspalast in Berlin after they had played in different rooms. Nevertheless, my assumption was that the players (despite the diversity of the rooms) will experience recurring behaviors and certain feelings when playing due to this specific situation.

To clarify the question about the effect of the space, I asked them the following question:

What feelings did you experienced when you entered the rooms, especially considering that it is up to your understanding of the riddle and your ability to solve those riddles whether you move forward or get „stuck“. The main thing reported was an „inspiring“ ambition, closely followed by curiosity about „what might happen next“. For most, the spatial effect was primarily characterized by something described and characterized by „imaginative interior design key elements“, which encouraged the desire to explore and discover. What else could be hidden behind this object? Here, a slide rule can transform into a casket and a small bottle into a key and no wall has to remain immobile.

Everyone was looking forward to experiencing and „immersing themselves in a small new world“. Most experienced great joy and motivation in the adrenaline of being „locked in“ and a huge motivation to master the necessary challenges. Every successful solved task gained loud approval and enthusiasm of the group as creative experimentation and logical thinking was mentally celebrated. A certainty was achieved that gave more and more certainty as knowledge increased. Each room tells its very own story thanks to the deliberate theme design.

In all rooms, the players became more mindful of their surroundings. The room was viewed differently than is usually the case. The opportunity for discovery led to a more thorough observation, familiarization and reflection. The meaningfulness of the individual objects and the choice of colors together with the furnishings thus provided the incentive for future next steps and trains of thought. All participants were visibly enthusiastic and felt good because they were able to recognize the puzzle strands and solved them correctly.

For this case the „game world“ was thus understood as intended by the riddle. Of course, some also felt almost „frozen“ and trapped when something didn’t work right away. The more people took part together, the more difficult the experience was perceived to be. The exciting thing was that many did not have the impression of a „game“, as the interior architects, designers and the like had presented and thought through everything so realistically.

This „extraordinary way of interacting with the space“ gave the players an authentic playing space, where the players themselves freely determine the order and exploration.

Those who signed up for a prison wing got one. Those who wanted to enter a strange magical world or wanted to experience the golden 20s, embarked on this journey. The adrenaline and the thrill of the unknown were correspondingly high. Even those who had difficulties and some frustration in solving the puzzle strands were at least positively impressed by the design and vivid spatial perception.

Above all positively, the rooms stood out when there was a kind of window somewhere.

The question was also whether a recurring principle of arrangement or a special form in those

Rooms stood out. Here, it was primarily the thematically appropriate design and the

sound, but architectural features or similarities were not even recognized at all. The unexpected, mobile architecture created a great surprise factor by opening objects or passages. This was so great that none of the players expected another room or „passage“ in certain places, especially not with such a different „look“.

Surprise: When the shape can be formed and a change of perspective is the result.

From my own gaming experience and observation, I can confirm that rooms like these appeal to every adventurous explorer. A successful room design thrives on deliberate uncertainty and the surprise factor when discovering and the resulting maximum gaming fun. The lively spatial effect and dynamic design is what makes the whole thing a special experience in which you can also train and recognize your own conscious use of space. It is a wonderful exercise to experience the notorious „oh – how could I have missed THAT!“, but also to overcome it by later entering other spaces more mindfully with a noticeable increase in attention.

Anyone looking for a lively spatial experience and creative encounters will find what they are looking for here.

The rooms, some of which are angled, have their own formal charm, but its effectiveness is only through their creative, thoughtful and colorful design.

A big thank you goes to all the players who happily agreed to share their feelings and thoughts with me after the games.