Space – Sensation – Design. Impressions of a weekend seminar on spatial experience

Thirty spokes support the hub,

But the emptiness makes the wheel usable.

The potter moulds clay into vessels,

the emptiness inside makes the vessel.

Windows and doors are broken into walls,

the emptiness inside makes the dwelling.

Thus the visible forms the shape of a work,

and the invisible makes it valuable.

Lao Tzu 1

1. Laotse, Tao te king, Spruch 11.

In architecture, there is a mysterious overlapping of space, sensations and consciousness. Spaces can create moods in us through their design and atmosphere and steer our consciousness in a certain direction. This is a mysterious phenomenon, because the spatial is actually something invisible. How is this possible and what triggers such sensations? Most of the time it happens largely unconsciously, but is it possible to make such sensations conscious and how do you do that? The weekend seminar ‘Space – Sensation – Design’, which took place from 8-10 March 2024 at Alanus University near Bonn, was dedicated to these questions. It was organised by the Section for Fine Arts at the Goetheanum in collaboration with the IFMA (International Forum for Man and Architecture) and the architecture department of the Alanus University of Arts and Social Sciences. The programme was divided into three parts. First there were three introductions with exercises on different types of spatial perception, then we tried them out on three special buildings in Cologne, and finally we analysed and deepened our experiences.

Introductions to spatial perception

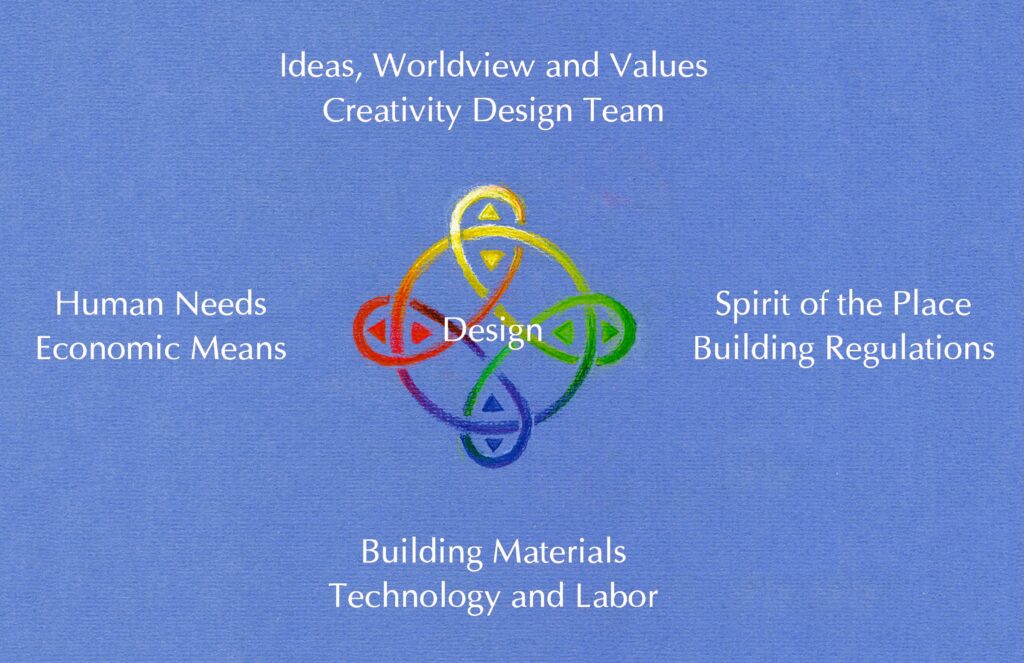

Three architects began by presenting their different methods of exploring space. The first to speak was Luigi Fiumara, Chairman of the IFMA, on the perception of architectural space in one’s own body. He referred to a statement by Rudolf Steiner in which he describes architecture as projecting the laws of the human body into space(2). If it is indeed the case that we project the laws of our own bodies into architecture, then surely we should also be able to feel the architectural design on our own bodies? To investigate this, different spatial forms were created using large sheets of corrugated cardboard. Some participants stood inside and tried to feel the qualities of the different spatial forms on their own bodies. They started with a triangular room. This triggered a feeling of restlessness in everyone. The room draws attention to the sharp corners and doesn’t allow you to calm down. This changes immediately when this triangular room is transformed into a hexagon. A calming effect is created immediately, and if this spatial form still has a tendency towards movement, it does not draw you outwards, but invites you to move in circles. In this way, each spatial form has its own character, which we can feel in ourselves as physical and emotional stimuli when we live in it and feel it inwardly. But how do we perceive these qualities? The contribution by architect Martin Riker was dedicated to this question. He used Rudolf Steiner’s theory of the senses with its twelve senses to help us understand the complexity, but also the holistic nature of spatial experience (3). He used a series of projected images of tables to illustrate the fact that the senses are not separate from each other and can also interact with each other. We were therefore not looking at actual tables, but only at projected images of them. All the impressions that these images aroused in us were therefore channelled through the sense of sight. Nevertheless, we were able to perceive qualities such as statics, dynamics, balance, warmth, texture, form, mood, etc. Willem-Jan Beeren, Professor of Art and Architecture at Alanus University, offered a completely different approach to spatial perception with his contribution on space as an experience of sound. Hearing is one of the higher senses and, in contrast to seeing, takes place in time. In hearing, we do not extend ourselves beyond the space, but allow it to enter us (4). This was also made tangible with experiments. We heard fragments of sound that made us involuntarily visualise certain spaces, such as a canteen or cafeteria. We also moved around the room speaking, trying to observe the transition from sounds to speech and from speech to mental meaning. Equipped with these different exercises and approaches, we ventured out the next day to look at three monumental buildings in Cologne.

An unintentional experience of depth

The aim of our excursion was to see three highlights of sacred architecture in Cologne. However, it began with an unintentional visit to four underground spaces. Our electric car needed a charging point and, hoping to find one there, we drove into the multi-storey car park at the cathedral. We crossed the car park but couldn’t find a charging station, so we drove out again after a few minutes. Fortunately, there was a second car park nearby, which we also drove into, searched and left again without success. Right next door was a third car park, which we drove into again, searched and had to leave again within a few minutes without success. That was when it started to get funny and we realised the connection to the subject of the excursion. We had travelled to Cologne to see three highlights of sacred architecture, but we had passed through various underground spaces in the city. We usually ignore such experiences. However, the fact that we had to pass through four buildings of this type one after the other suddenly made us realise the special character of these places. They were all low and dark, with no pretence of design that went beyond purely functional purpose fulfilment. Their narrowness, lowliness and dirtiness gave them all a somewhat eerie atmosphere. You would never think of staying there, but would want to leave the space as soon as the car was parked and only return when you wanted to drive out. Once we were up there in the sunshine and the cathedral was shining brightly in front of us, we breathed a sigh of relief and realised how beneficial the fresh air and warm sunlight were. However, it was an interesting preparation for our excursion to realise how rooms can be ‘deprived’ and ‘enriched’ by natural elements such as daylight and spiritual qualities.

Cologne multi-storey car park © Pieter van der Ree

from the south © Pieter van der Ree

Up into the light

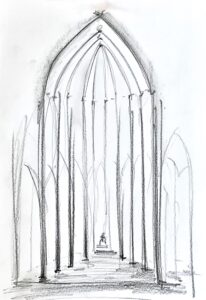

Cologne Cathedral is visible from afar and shows travellers where the centre of the city is located. As you get closer, the surrounding buildings soon obscure the view of the cathedral until, when you get very close, it suddenly reappears in its towering grandeur. As you enter, you are involuntarily enveloped by a kind of concentrated silence. The mighty height, the rhythmic bundles of pillars, the coloured windows – they lend the room a grandeur that almost everyone can sense and that casts a spell over everyone. However, we intended to consciously explore the space. To do this, we split into three groups, who looked at the room from the angles we had practised the previous evening. One group focussed on the acoustics of the room, the second let the room affect all the senses and the third tried to feel the effect of the room on their own bodies. After half an hour, we exchanged our experiences and switched to the other group. One of the first fruits of this approach was that we became aware of our usual way of perceiving space. Instead of letting your gaze wander at will, you had to concentrate on a specific aspect. However, you were constantly distracted by interesting details or other visitors. All these visual impressions prevent you from paying attention to the sound of a room, for example. But if you try to do so, a new world opens up. Even with your eyes closed, you can sense that you are in a very high, structured room. If you move around listening, you will notice how different the sound is in the nave, the side aisles and the crypt. Above all, however, this crypt has a completely different sound and atmosphere to the underground car parks you have just visited. What was particularly noticeable was the uplifting power of the space, especially in the central nave. The mighty bundles of pillars appealed to our own verticality, whereby the threefold structure of the wall in the choir resonated with the threefold structure in our own body: the coloured windows in the upper area with the head and chest area, the middle zone with the stomach area and the lower area with its continuous pillars with our own legs. What leads up to the light when looking towards the east, above the altar, works in the opposite direction towards the west. There, before leaving the cathedral, the mighty bundles of pillars bring visitors back down to earth with their two legs.

towards the choir © Pieter van der Ree

towards the west entrance © Pieter van der Ree

An ambivalent space

In the afternoon, we visited St Gertrud’s Church in Cologne’s Neustadt district. It was designed by the architect Gottfried Böhm in 1960 and built between 1962 and 1965. Unlike Cologne Cathedral, it is not a free-standing church, but one that is embedded in the surrounding buildings. The two buildings are also very different inside. On entering St Gertrud’s Church, the eye first has to get used to the darkness. Then an asymmetrical, open-plan space becomes visible. Although the entrance is opposite the chancel, the spatial effect is not axial, but rather rounded. There is no clear spatial direction, as we experienced in the cathedral. As a result, we needed some time to orientate ourselves in the room. We tried to do this from several different places, but without any success. After a while, we realised that this probably had to do with the fact that the functional direction of the room, which is clearly oriented towards the altar and the crucifix hanging above it, and the architectural direction of the room, which runs more in the transverse direction, contradict each other. The mighty, crystalline folds in the dark concrete roof cross the orientation towards the altar and rather convey a transverse spatial direction. At the top left, the roof rises above three crystalline windows, while on the right it rests on a flatter wall that serves for two confessionals made of raw concrete. If you look up from these confessionals to the windows, the room has a harmonious effect, but the altar area is ignored. So we struggled to understand this independent and expressive space, but did not succeed well. Did the confessionals perhaps have a much greater significance in the post-war period than they do today? We felt our way in, but couldn’t find the key. Just before we were about to leave, our eyes fell on a poster with a quote from the architect: ‘I didn’t actually want to build a sacred space at that time after the war […] I was a believer, but I was completely against this sacred atmosphere, I rejected it. Strangely enough, it is now the case that although people have stronger doubts and resistance to faith, they tend to recognise the value of the sacred again.’ Was this perhaps the inner reason for the ambivalence of the room that we felt here? However, we were puzzled as to how it is possible for such an inner attitude to be reflected in the architectural design and still be experienced decades later and cause problems for visitors. In the meantime, as posters testify, the church management is also looking for an extended purpose for the church as a cultural space.

Design by Gottfried Böhm, 1960 – 1965 © Pieter van der Ree

towards the altar © Pieter van der Ree

North facade © Pieter van der Ree

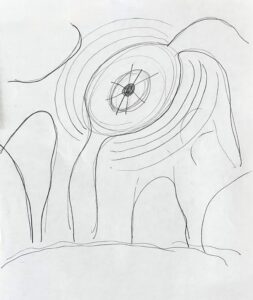

Golden doctrines in the domed room

There was no sign of such ambivalence at the DiTiB central mosque in Cologne-Ehrenfeld, which we visited at the end of the afternoon. Completed in 2017 to a design by Paul Böhm, the son of Gottfried Böhm, the building appears lively and seems to fully fulfil its intended purpose. The mosque is located on a thoroughfare and is visible from afar with its 35 metre high dome and 55 metre high minarets. The mosque is part of a larger building complex with an underground car park, a shopping centre, offices, cafeteria and ritual washrooms. The above-ground functions are grouped around an elevated inner courtyard, which is accessible via two wide staircases. The design of the surrounding courtyard buildings is rectangular and simple, with the actual mosque clearly standing out due to its rounded shapes. It consists of six domed segments rising towards the centre with glass strips in between, which let in daylight and contain the entrances. Although the mosque is freely accessible, it can only be visited by groups on a guided tour. This was provided by a student who informed us about the design of the building as well as its religious background. He told us that the two central tenets of Islam: ‘There is no god but Allah and Mohammed is his prophet’ are inscribed in elegant calligraphic script on the two wooden entrance doors and thus mark the entrance to the true faith. Inside, the walls of the prayer room are also decorated with golden letters using calligraphic texts from the Koran and the names of the arch-fathers. Otherwise, there are only geometric decorations and, unlike the cathedral and St Gertrude’s Church, the room is free of pictorial representations. Another contrast to these two buildings is that the building envelope of the mosque consists of rounded building elements. These have curved edges, as if they had been loosely cut out of the domes. If you try to feel the whole thing in your own body, you will feel it most strongly in the head area. The doctrines that surround the believer in golden letters also appeal to the head. They are revealed and traditional beliefs that are constantly visualised. At the very top, at the zenith of the dome, there is a round light opening with a ten-pointed star in it, which represents Allah and is intended to make it possible to experience how his presence is always close at hand. The soft, light blue carpet, which covers the entire interior and gives it the character of a huge, communal living room, is particularly evocative. Shoes must therefore be removed before entering the room. The carpet lifts the room from the everyday into an elevated sphere and at the same time makes it more comfortable to prostrate oneself on the ground in prayer. This ‘throwing oneself on the ground for Allah’ is the central gesture of prayer and the architecture supports this gesture with its formal language. It guides the curves of the domed segments down to the earth in a flowing movement, just as the worshippers themselves bend towards the earth. In other words, a harmonious combination of inner attitude, ritual action and architectural gesture.

Design by Paul Böhm architects,

2006 – 2017 © Pieter van der Ree

DiTiB Central Mosque Cologne © Pieter van der Ree

DiTiB Central Mosque Cologne © Pieter van der Ree

Organisation and religious feeling

The next morning, we looked back on our experiences of the previous days. Firstly, we tried to draw the three buildings we had visited from memory. Of course, this was only possible to a very limited extent, but each participant nevertheless managed to capture some characteristic design elements. The overall result was amazing, however, because despite a lack of memory and drawing skills, very clear, unmistakable features emerged. The buildings visited could be characterised with a few slanted or curved lines. Apparently, we recognise buildings by such features and sense their character from them. During the conversation, we realised topics that we had just tried to ignore the day before. We had concentrated on the spatiality of the buildings and not allowed ourselves to be distracted by other visitors. In reality, however, they were there and we were well aware of them. They coloured the memories and added an essential element. In retrospect, I realised that the use of the three buildings was very different. Although there were many visitors to the cathedral, they were mostly tourists who had come less for the church service than for the impressive architecture. When we entered St Gertrude’s Church, it was initially completely empty. We were the only visitors for quite some time. After a while, a couple of people looked cautiously around the corner, apparently saw nothing of interest and disappeared again. The mosque was the only one that functioned as intended. It was also the newest building and had only been completed seven years ago. What this observation taught us was that even if a room design is initially seamlessly adapted to its intended use, the religious sentiment behind it can change and the context can become detached as a result. This does not necessarily mean that the building loses its value. It can also be transformed. The cathedral still forms the centrepiece of the city and can still convey very valuable experiences, even if the religious experience has changed. Indeed, it is even a special quality of architecture to capture such past religious feelings and ideas in stone, allowing us to relive them centuries later.

Design and identity

For many architects, it is a high goal to create spatial forms that are functionally and sensitively suited to their use. In the buildings we visited, this was currently most strongly the case with the mosque. Nevertheless, I felt a certain inner reservation. Although some of my architectural ideals were fulfilled, I couldn’t quite identify with them. Where did this come from and how did I know for sure? It had nothing to do with judgement, I just felt that it wasn’t my way. Apparently we can feel the character of external forms and their relatedness or strangeness in relation to our own identity. This experience has little to do with an aesthetic judgement. I can find something beautiful, but it can still be alien to me. It can be an artistic masterpiece and yet it is possible that I cannot identify with it. Apparently, there is a kind of ‘sense of identity’ that allows us to perceive both the character of visible objects such as buildings and our own, completely invisible identity. It was an unexpected and fascinating experience that we realised in these buildings.

of Cologne Cathedral © Pieter van der Ree

of St Gertrude’s Church © Pieter van der Ree

of the DiTiB central mosque © Pieter van der Ree

Unexpected shifts and new insights

Were these the most important fruits of this weekend seminar? They were certainly valuable, but probably even more important was the experience that it is possible to deepen one’s own spontaneous experience of space and become aware of it. Usually a large part of it passes us by unnoticed. By becoming aware of them and sharing them, unexpected layers and insights opened up. What at first glance appeared to be subjective impressions usually turned out to be shared perceptions. Although people experience things individually, this does not mean that the experiences are only subjective. One’s own perception can obviously be developed into a kind of organ of perception. This requires practice, both in perception and in the articulation of what has been experienced, but is evidently an accessible and very enriching path. The disadvantage is perhaps that the experience is not objective in the usual scientific sense. The advantage, however, is that you educate yourself in this way. Where else would an architect draw inspiration from when designing? And how can you create sensitively harmonised spaces for your client if you haven’t developed a feel for them yourself beforehand? So the seminar was above all a confirmation of the importance of developing new organs for perceiving and sensing spaces and an incentive to practise on this path. How these skills can be put into practice when designing, how working behind the computer affects these skills and what new skills this design work requires of us are questions for the next weekend seminar.

2 Rudolf Steiner: Kunst im Lichte der Mysterienweisheit, GA 275, Dornach 1980, S. 43.

3 Rudolf Steiner: Zur Sinneslehre, Stuttgart 1980.

4 Juhani Pallasmaa: The Eyes of the Skin, Architecture and the senses, New Jersey 1996.