The 12 Senses – the basis of spatial perception

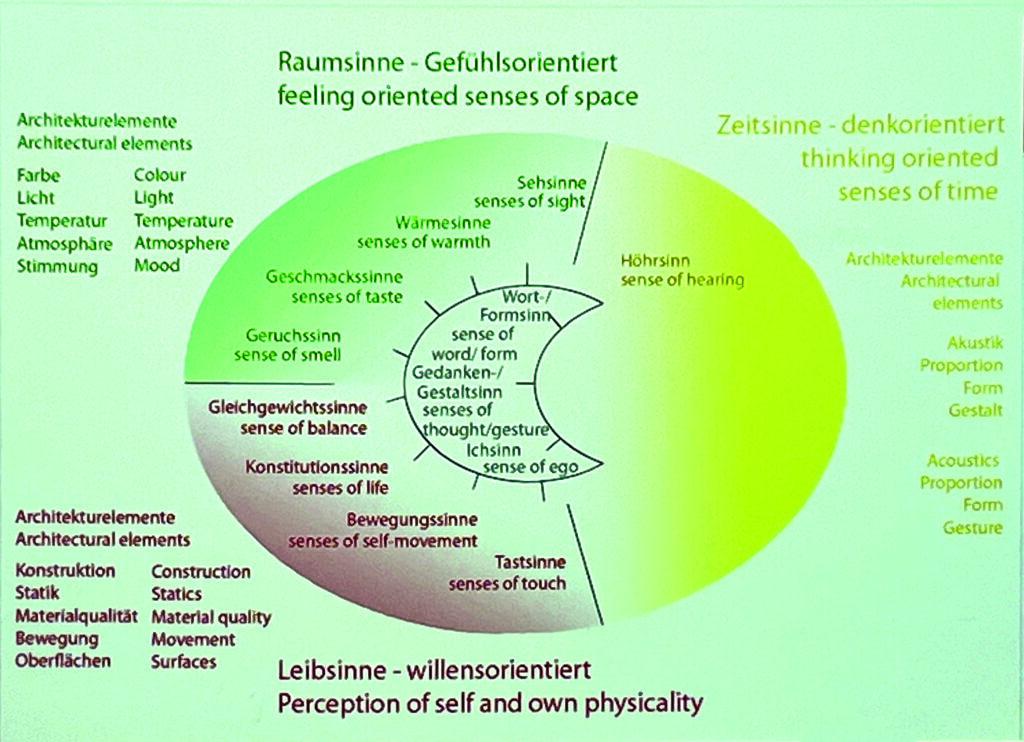

Without the senses, we have no perception of this physical world. Our senses are the gateways to the world. We use our senses to anchor ourselves in the world as human beings and thus experience a sense of security and integration. We must learn to structure our sensory impressions and develop more awareness in sensory perception. This is an important basis for our work as architects and designers. After all, our senses are the organs with which we perceive architecture. I would like to show a way to develop more awareness – and also more precise concepts – for sensory perception. What we experience in perception as a complex unit must be differentiated and structured. For the multi-layered areas of sensory perception, we have the most diverse organs of perception that we need to know. Only in this way we´ll be able to categorize and evaluate our perceptions in a fruitful way. Every perception always involves several senses working together, with one sense having the leading function. This guiding function is closely linked to our intentions, to what we focus our senses on, what they are attracted to. Physiology today speaks of around eight to ten senses, but these are not very differentiated and delineated. Rudolf Steiner developed a conclusive concept of twelve senses between 1909 and 1924 and assigned them to the human being’s essential elements (body-soul-spirit). On this basis, there were many in-depth studies, e.g. by Willi Aeppli in his book “Sinnesorganismus, Sinnesverlust Sinnespflege” (Willi Aeppli: Sinnesorganismus Sinnesverlust Sinnespflege. Rudolf Steiner’s theory of the senses in its significance for education, Stuttgart 1979) in connection with educational issues. Hans Jürgen Scheuerle made a significant contribution to the relationship towards architecture in his work on the overall organization of the senses (Jürgen Scheurle: Die Gesamtsinnesorganisation, Stuttgart 1984) and to the concretization of the modalities. For me, this approach is an essential basis for consciously dealing with the senses and their relationship to the elements of architecture. The twelve senses are the sense of touch, the sense of life, the sense of movement, the sense of balance, the sense of taste, the sense of smell, the sense of sight, the sense of warmth, the sense of hearing, the sense of speech, the sense of thought and the sense of self. In the following I can only give examples of individual senses. These twelve senses are divided into three groups or modalities: the physical senses, the spatial senses and the temporal senses.

The body senses

We can call the first four senses the bodily senses. They give us information about how we relate to the world with our physical body. They are the senses of self-perception or body perception (the red part of the diagram). Let’s do a little exercise here. Pick out a small object, e.g. a small stone. Feel what you experience: Pressure on the skin, pointy or smooth – this is a tactile experience. For the tactile experience, you must constantly move the object, i.e. activate your sense of movement. But you also experience something else, the heaviness, the weight of the stone. You experience this with the sense of life. And you also experience the temperature: is the stone cold or warm, is the sun shining on it? This is where we experience the sense of warmth. You can see how varied this little tactile exercise is and how we also activate the other senses involuntarily. The sense of balance tells us the position of our body in relation to the spatial directions: left, right, front, back, up, down. The sense of movement provides us with information about the position of our body and limbs and registers changes in position. We perceive external movements by following them internally in our body. We find the organ of the sense of movement in our musculature, in the shortening and lengthening of the muscles. This is how we perceive movements and forms outside ourselves through the muscles in our eyes.

The spatial senses (green marked)

The next group out of those twelve are the sensory or spatial senses: the sense of taste, the sense of smell, the sense of sight and the sense of warmth. They convey mental impressions to us. The sense of smell, for example, tells us what is in the air. In a room, for example, it warns us if we smell a burning smell. The sense of smell is always active, but we only become aware of it when there is a change in the environment. Nevertheless, it is very present when we enter a house, for example, and are confronted with a certain smell. A smell that we know from another situation, e.g. from our childhood, from our grandparents. If we now follow this perception, we find ourselves in our grandmother’s house with all the emotional sensations of that time. The olfactory experience is strongly linked to the room and place and our earlier experiences. This emerges from the semi-conscious, our consciousness has no direct access to it. Our sense of sight is our guiding sense, especially in today’s visually influenced culture. We perceive colors, light, bright and dark, contrasts, but also shapes and formats. We have a clear sense organ, but it conveys more to us than just the visual. We can see how complex the subject is and that “seeing” is not just limited to the optics of the eye. We have visual perceptions that immediately evoke sensations. With this group of senses – sense of taste, sense of smell, sense of sight and sense of warmth – we open up space. We leave our body. We feel ourselves in space, we actively connect with our surroundings. We can also call them the spatial senses.

The senses of time (yellow marked)

The next group of senses are the senses that extend beyond space, the senses of time. Their qualities can only be experienced in time. These senses are closely related to the volitional senses of our bodily or self-perception. They require the abilities of the bodily senses, but the direction of perception is directed outwards through our consciousness towards our fellow human beings, towards the animated and essential. Against this background, we can also refer to this group as the social senses. It includes the sense of hearing, which forms the transition from the feeling-oriented to the thinking-oriented senses, the sense of speech, the sense of thought and the sense of self. A piece of music or a conversation cannot be captured, it develops on the timeline. We have therefore become familiar with three sensory or modal areas: the physical senses, the spatial senses and the temporal senses.

Senses and the relationship to architecture

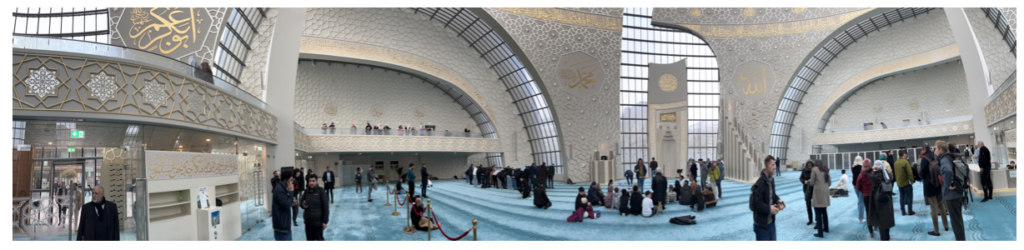

In the following, the references to architectural perception and architectural elements will be briefly outlined. As a rule, we remain completely unaware of our bodily senses. They anchor us in the world and allow us to experience the qualities of architecture directly in our own bodies (see diagram). If everything is harmonious and nothing throws us off balance, we are usually not aware of it. We move safely in the space, but have no conscious experience of our bodies. The architectural references to these senses are the spatial directions, the construction and statics, supports and loads, the dynamics in the space, the materiality, the natural, structured material, the surfaces. The following examples illustrate this well: If we are in a room with vertical windows, we can feel these verticals in our back and in our spine. We are straightened up. If the room has “horizontal” windows, we can feel the need in our body to move into a horizontal position. If we look at sloping pillars, an activity is generated in us to bring ourselves upright against this slant. We experience the need to restore the vertical. We are usually not aware of these perceptions, but they have an effect on us. As the example of the sense of smell shows, we are only half aware of our perception of the spatial senses. They only enter our consciousness when we direct our attention to them, but they still create an indirect, unconscious impression. For example, we perceive odors as described above when they create a great difference and discrepancy to our expectations. So there is something unexpected. The sense of temperature or warmth also only comes into our consciousness when we feel cold or too warm. We are only partially aware of the activity of our sense of sight. For example, when we are driving a car, we perceive very few things consciously. Who can say afterwards the color of the house that we drove past if it didn’t catch our attention? We can assign special architectural perceptions to this sensory area. Smells, colors, light and shadow, room temperature and mood are the elements in architecture with which we experience the atmosphere, the perception of space. Let us illustrate this with an example. Imagine entering a room painted in vivid terracotta, where the light falls in through a window and the window bars draw shadows on the blue-grey terrazzo floor. We feel the protection and warmth of the walls and the coolness of the floor – color and light make us feel cheerful. “Our hearts open up.” Our attention is usually required to perceive the senses of time. These are the senses that are only active with awareness. We use these senses to perceive the following architectural qualities: the sound of the room, the proportions, the shape and form, the idea of the room and even the essence of the building. When we allow the impressions of the previous senses to take effect on us, the room speaks to us. Through our own speaking or singing in the room, the room responds through its acoustics, its reverberation or its acoustic dullness. We experience the regularity of its proportions and we sense the shape of the room.

Awareness in perception

If we want to practise this deeper perception of architecture, we need to develop more awareness, especially for the perception of the physical and spatial senses. After all, they also form the basis for the higher senses of time. Without awareness of our own bodily perception, we cannot classify our sensory experiences. We lack the basis for understanding how space affects us. However, this is the basis for consciously using architectural qualities when designing architecture. In the visual perception exercise, we have seen that we are initially drawn out towards the object, but are then thrown back into ourselves. We compare the image with our earlier perceptions, the concepts we developed from them and our ideas. We then project these back into the world. If we want to develop our perception further, we should proceed with the following intention. Let us extend our visual process, leave behind our intentional gaze for individual details and move around the room with an expanded vision, trying first to sense and then to raise our awareness of what the other senses are showing us. It will be an exercise to remain completely in perception, to expand the pure process of perception. For example, when seeing, to observe exactly what is happening, which other senses are involved. Where do resonances arise in our body, in our sensations, in our cognitive life? If we try to stay in the space with our perception for as long as possible, we can experience that new things also emerge, as our ideas do not immediately close off the perceptual space. We must practice expanding our perception, immersing ourselves in our perception, controlling our flow of thoughts and protecting ourselves from quick judgment and concepts, increasing our consciousness, our awareness. It is a simultaneous experience on three levels. Through the body-related senses I have the perception “I am within myself”, through the space-related senses the perception “I am in the world, in space” and through the time-related senses “I am in the flow, stream of thoughts, in the presence of mind”. If we manage to keep our sensory attention in space with full awareness and endure the tension, we will be able to observe that something is coming towards us from the future, the timeless space of thought, that something is opening up. In architecture, the building idea, the essential, can reveal itself as the essence of architecture.

Further reading:

– Wulf Schneider: Sinn und Un-Sinn – Umwelt sinn-

in architecture and design,

Wiesbaden / Berlin 1987.

– Rudolf Steiner: Themes from the Complete Works 3,

On the theory of the senses, Stuttgart 1981.

– Arthur Zajonc: The shared history of

Light and Consciousness, Hamburg, 1997.