At the moment, day-care centres are being built everywhere. When one sees the results, the question often arises: Who was this built for?

The day-care centre has the task of creating space for the healthy physical, social and mental development of the children. A space in which the educators accompany the pre-school children in their development to settle into the world and to be able to understand it.

So far, architecture has only gone beyond fulfilling functional requirements in a few areas. Only in Reggio and Waldorf education do we find design approaches that have developed out of pedagogy. The purpose of this paper is to present the relationship between the child and the architecture and its pedagogical effect. This is all the more important because in recent years the developmental environment of children has shifted from family education to crèche and all-day care.

First, I would like to delve a little deeper into the basics of pedagogy and human organisation in order to then understand the impact and requirements of architecture.

History

What we understand as a day care centre today encompasses the crèche from birth to 3 years of age and the kindergarten for children from 3 to 6 years of age. Historically, both facilities date back to the beginning of the 19th century. While the crèches developed from the infant’s and children’s homes for the poor and orphans, the kindergarten developed from an educational pedagogical approach. In the middle of the 19th century, Friedrich Wilhelm August Froebel founded the first kindergarten in Germany. The aim was to support the family in raising children.

At the beginning of the 20th century, new impulses came from education reform. Rudolf Steiner, for example, expressed his views on child development and pedagogy in a wide variety of writings. Maria Montessori also influenced developments in education through her observations.

Under National Socialism and later also in the GDR, the educational mission was ideologically abused. In the post-war years, due to broken families and the necessity for women to work, the care of children was a major focus of kindergartens.

Pedagogy

The pedagogical concept was to educate the children for a life in society and to prepare them for school. It was not until the sixties and seventies that further developmental psychological viewpoints were integrated into the pedagogy. Only the impulses of the Reggio pedagogy from Italy should be mentioned here. For the crèche sector, the paediatrician Emilia Pickler gave essential impulses through her observations of children in care. As a result of the new pedagogical evaluation, the kindergarten was declared the first stage of the education system in 1970. The approaches to nursery education today are essentially based on the pedagogical and psychological observation of child development. The perception of children’s needs is thus the basis for a wide variety of educational concepts in the crèche sector. In “Das Kinder-und Jugendhilfegesetz” (KJHG 2007) §1 it says, “every young person has a right to the promotion of his or her development and education and to become an independent and socially competent personality”. This is now a social consensus.

The human being is in many ways a premature birth and therefore not determined and so open in his development! In order for children to develop, they need protection, security and warmth in their environment, in continuation of the mother’s womb. Helpful here is Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophical view of the human being, which from a spiritual-scientific point of view can add further aspects to the developmental process of the human being. Thus, we can also understand the whole process of development as a process of incarnation. The child as a spiritual being works its way into its body.

Rudolf Steiner explains in his lecture “Pedagogy and Morality” 3/1923 (Anthroposophical Study of Man and Pedagogy) that the first three years of life are more important than all the following phases of development. He points out the importance of learning to walk, learning to speak and learning to think and how the child organises itself into the world. By settling into the world, according to Steiner, the inner organs are formed as the basis for being human. Then, until the change of teeth, the child lives completely devoted to its environment. As an imitative being, it makes the outside world a part of itself. Steiner is quoted here once again: “It wants to imitate what the adult does. What matters in kindergarten is that the child must imitate life”. (In “The Pedagogical Practice from the Point of View of the Spiritual Scientific Knowledge of Man”. Lecture “Play and Work”, 18.4.1923)

The scientific observations of brain research in recent years confirm this insight. The importance of early childhood experience for development in later life has been systematically elaborated in our time. All organs and senses are formed by the environment. The human brain also receives its internal characteristics and interconnections during this time. This is confirmed today by development and brain research, for example by Gerald Hüther.

In the phase of life from one to seven years of age, i.e. in the elementary area, we can observe two essential developmental steps. In the first three years, the child takes hold of its body. It develops from a helpless being lying on its back to an independent human child moving in space. In the phase of life from three to six years, the child begins to understand, experience and conquer the world. This development does not take place in a linear fashion, but in cycles of development, in metamorphoses, which continue in a transformed form after reaching a certain stage of development.

In the first stage of human life, between birth and the age of three, the small child acquires motor control over the limbs. Once it has reached this stage, it will try to move about, crawl, sit up and stand with tireless activity and get into an upright walk. This acquisition of the basic human posture is a constant struggle against gravity. Through this activity, right into the physical, the organs are reshaped and adapted to the upright gait. The child has thereby gained the freedom to act creatively with his hands. This is the basis for the exercise of all human abilities, the learning of language and, building on this, the ability of thinking.

In order to awaken this impulse in the child, the adult human being is the role model who, in his or her I-ness, makes this overcoming of gravity an experience. Without people in its environment to give the impulse, it will not make this effort. Standing on the earth strengthens the basic trust. The earth carries me. Development always continues on in its own initiative, there is no standstill. Once the balance has been conquered, the first steps are already taken. As soon as the world can be grasped, the first concepts are formed, which are the basis for thinking. Thus, grasping in the truest sense of the word is of fundamental importance. The child develops its own language to deal with the environment. In this way, it places itself in the culture into which it is born.

In the second stage of development, i.e. from the age of three until the change of teeth or the beginning of school, when the child can experience itself as a self, it is ready for “kindergarten”. Children open up to the world, they need the adult as a role model in order to develop further by imitating him or her. This develops their senses and abilities to face the world. Through language and its rhythmic musical quality, the child also experiences the differentiated mental expressions of the adult. For this self-development, the child needs role models, but also time and space and stimulation from the environment. With the change of teeth, this process of organ formation comes to a certain conclusion.

The Relationship Between Human Beings and Space

The process described above is made possible by the people in the environment, by parents, teachers and also by the architecture. The rooms not only form the third skin of the human being, but also have an effect on the child.

This exciting interaction between self-activity and impulses from the environment has led to the room now being recognised as a third educator. In 2008, the competition for the “Invest in Future” prize for innovative pedagogy focused on space as the third educator. The architecture must be designed in accordance with this task.

Particularly in our day and age, when children’s basic opportunities for experience are severely limited by our culture, architecture has an important role to play in supporting pedagogy. It must compensate for the natural living environment.

Despite many debates about pedagogical concepts and effects on child development, the spatial conditions are often not discussed. However, the needs of the children should be the basis for the qualitative requirements of the rooms.

How does architecture affect children in different areas?

The bridge here is our sense organs with which we perceive the physical world and connect with the world.

The following diagram is intended to clarify the relationship. It is based on Rudolf Steiner’s depictions, who divides the human body into three areas, head, chest and limbs. With the limbs, the human being places itself in the world, connects with it. In the chest area – the rhythmic system with heart and lungs – the soul’s own life develops; a first freedom is attained. The development of concepts and ideas is related to the head. Here we again recognise the three-step process already described above.

We can assign sense organs to these three areas. For this we can refer to the sensory theory of Rudolf Steiner’s theory of the senses in “Allgemeine Menschenkunde als Grundlage der Pädagogik”, in which he develops twelve senses and relates them to the body. Willi Aeppli has worked out these relationships in detail in his book “Sinnesorganismus, Sinnesverlust, Sinnespflege”. It is shown that the child at this age is completely SENSUAL with its organism. It should be noted that sense perception is not one-dimensional, at least two other senses resonate. By understanding the relationship of perception to our bodies, we can then draw conclusions about architectural qualities.

It is the physically volitional and basal senses, the sense of touch, the sense of life or vitality, the sense of balance and the sense of movement, that develop first in the first three years and lay the foundation for further development. The equivalents in architecture for these areas are surface, material quality, building biology, construction, statics and movement dynamics. It is the surfaces with which the little human being first comes into direct contact in order to understand the world. The material qualities must be honest and authentic, otherwise the senses are corrupted. How can the material quality of wood emerge on a beech wood plastic imitation? The surface is always equally smooth and repellent, the sound dull. How beautiful can a piece of beech wood be, with its oiled surface and its sound revealing its inner structure. We must also consider the health aspects, just think of the plasticisers in plastics or toxic paints. If we take the guidelines from pedagogy seriously, we cannot use such products.

The construction in its load-bearing and static function should be honest and comprehensible. The vertical must be emphasised to enable the child to perceive its own uprightness. The spatial directions of front and back, right and left, up and down must be clearly shown in order to provide support and orientation for the first movements. The scale of the architecture and its proportions should be based on the laws of the adult human being. In this way children develop basic trust in their environment. A firm standpoint is a prerequisite for the development of the sense of balance in the first phase. Only in this way can spatial orientation succeed. The floor plan should therefore be clear and preferably symmetrically oriented. Of course, emotion-oriented senses also develop during this time. Good acoustics, for example, is a prerequisite for understanding each other and learning language.

Some well-intentioned attempts to design architecture suitable for children, such as a day care centre as a sinking ship – day care centre in Stuttgart Sonnenberg by Benisch, or a childlike “dwarf architecture”, are detrimental to development. They disturb sensory development with unexpected consequences.

Why are the demands so high today? Didn’t children develop well in the past? Today, the day-care centre has to compensate for the lack of a natural environment in our society and civilisation. A spiritually fulfilling artistic design that is meaningful and comprehensible is necessary for this. The living space seized by the educators becomes a model and impulses one’s own creative powers.

Room Concept for the Crèche Children

The room should offer security, support and orientation, provide stimulation and impulses and have the character of a call to action. From the pedagogy, three zones result for the toddler area, which are to be designed differently, the active area, the care area and the rest/sleep area, divided into at least two rooms.

The movement area with stairs and ramps has a special attraction for children of this age.

The architecture must become a mirror of experience of the child’s own body in order to develop the senses properly and to calibrate them for life. For the crawling children, this space should be limited once again so that they do not get lost. Facilities according to Emilie Pickler offer further impulses to be active.

The care area as a protected zone, with nappy changing, should be well planned. This is the area where the child alone receives the attention of the educator. Everything should be placed in such a way that there are no distractions during routine activities. Does the educator have to lift the children on the changing table? With ten children, this is already a considerable burden. So, it is good if the older ones can already climb onto the changing table on their own with a small step. The child should be able to be changed lying down or standing up. The washbasin should be close by. The change of clothes and nappies are in the school baths under the changing table for each child, i.e. within reach. Warming lamp above the changing area for the little ones. If everything is well organised, the educator can concentrate fully on the contact with the child.

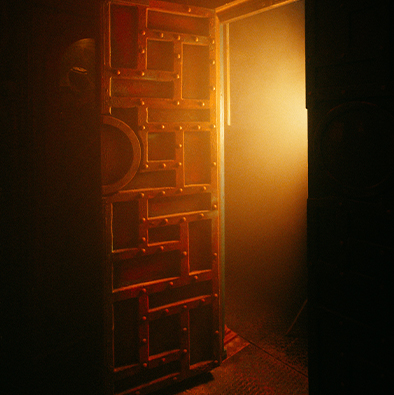

Photo Nappy-changing area closed and open

The sleeping and resting area should be muffled by fabrics and an acoustically effective ceiling and darkened by curtains or blinds. Each child has his or her own individual, protected sleeping space to be able to come to rest. This is very important for today’s children and can be achieved by designing children’s beds, sleeping bunks or platforms.

Room Concept for the Over-Threes

Mental self-life develops in role play, e.g. building, painting, handicrafts, preparing meals, eating together or listening in a story circle. The room forms a free-flowing envelope that demands self-activity. It should be divided into zones for the different activities. With today’s group sizes of more than 20 children, it is important that the individual groups do not disturb each other. The children must be able to immerse themselves completely in their own experience of their own spiritual development through imagination. These room divisions have a stronger effect if they are supported by designs on the floor plan and by different ceiling heights. It should be possible to adjust the brightness in the room in relation to the activities. For example, a completely different lighting atmosphere is required for the storytelling circle than for the area where the handicrafts workbench would be located.

How can architecture support the development of the child and the work of the educators? Here are a few comments on the elements of the room.

The floor must provide secure support so that the children can stand up. Then material and colour must be chosen. The most suitable material is cork flooring dyed with reddish oil. It is slightly elastic, warmer in surface temperature and easy to clean. Unfortunately, it is not as hard-wearing material and should be used with slippers or soft shoes. Linoleum flooring is an alternative for more demanding areas. The reddish brown or even green colour offers children a safe ground for development.

The walls are solid and immovable, supporting the ceiling and roof. They form the protective space for development. A fine plaster structure shows the materiality on the surface. However, it must not be too sharp grained. By forming rounded window reveals and wall edges, we have increased the perceptible solidity of the wall. The wall is the main carrier of colour and room colour mood. Through a wall glaze, we thus create a protective space that is open to the child’s development and conveys a sense of security. With a skirting board that matches the wall colour, the wall stands well and firmly.

The ceiling closes off the room at the top; it should protect but not oppress. A horizontal, straight ceiling often has an oppressive or sagging effect, especially if it is too low. This can be counteracted by making ceilings vaulted or even more sculptural. This creates a feeling of inner freedom and uprightness. However, it is important that the ceiling rests on the wall and is supported by it. If the glaze of the wall is also carried over the ceiling, this forms a good colour envelope for all activities. The ceiling is usually also the support for the acoustic measures.

The windows should not be too large and should have vertical formats or be vertically structured, then the uprightness can be experienced on them. The window parapet, preferably at different heights, closes the room and creates an intimate envelope. Without a balustrade, the room flows outwards. It is nice to have lighting on several sides, this increases the plasticity and sensuality. Bars in the windows let you experience the course of the sun through the movement of the shadows in the room. The different sill heights create protected zones on the floor as well as in front of the window. Low window sills invite you to play or sit on them, to observe what is happening outside, perhaps to dream after the raindrops. High window sashes, on the other hand, can only be operated by educators for necessary ventilation and creates security and allows the decorations to remain on the window sill. Movable coloured blinds and curtains can be used to control the lighting mood, intensity and colourfulness in the room, depending on the activity.

Light has a relationship to consciousness; it can be sunlight and artificial lighting. The way we deal with light has an important role to play in the mood of the room. In the light we wake up, we are out of ourselves with our senses. In order for the children to be able to develop in a protected way while dreaming, the light in the crèche area should be subdued, not too bright. The children should be able to concentrate on their physical development without too many distractions from the environment. After all, this is still about the body’s own perception.

For older children, the light should be adapted to their activities. This creates a tension between subdued, warm light for dreaming and listening to stories and cooler, more shadowy light for working.

Natural lighting is to be preferred. Artificial lighting should fully support and complement the quality. It is good if the lighting can be dimmed, even better if it can also change its light colour. As a substitute for incandescent light, we can use a combination of halogen and LED luminaires and thus control the light colour quality and intensity.

Colour

In any case, a colour concept should be developed for a day-care centre, which, like the architecture, is based on the needs. The colour concept enlivens and enhances the experience of the architecture. Here, colour has nothing to do with taste. Colour appeals to people in the emotional area and gives the rooms a quality of sensation. The choice of colour for the day-care centre results from the basic theme of the envelope and the use in this extended sense. For the group rooms, a free-form, envelope-creating basic colour scheme between pink and salmon colours should be chosen, which integrates walls and ceilings. In the corridors and cloakrooms, the colour scheme can give impulses through colour changes. After all, there is life and movement here.

A differentiated colour design is possible through the glazing technique. The colours are applied in several transparent layers of different colourfulness. In this way, a strong colourfulness can be created that is not oppressive. The wall surfaces appear lively and are strongly influenced by changing light moods. A variety of constantly new, invigorating sensory impressions are created. The changing incidence of light during the course of the day enlivens the colour effect of the glazing technique. The narrowness and expanse of activity and retreat areas are supported and intensified by the colour scheme, thus making the functional areas perceptible on all levels of perception.

The acoustics in the day-care centres have been neglected for years. The noise level with 24 children is actually only bearable with hearing protection. This became noticeable when the hearing loss of the kindergarten teachers increased. Especially for language learning, good intelligibility in the room is a prerequisite. But also, so that the children can pursue their various activities without disturbance and distraction. The easiest way to control the room acoustics is through an effective acoustic ceiling.

The Educator’s Workplace

We must not forget that the kindergarten is also the educator’s workplace. In addition to legal regulations and ordinances, their needs must also be taken into account. The workflow in and in front of the group room should be well organised so that there is no stress when working with the children. It should be designed in such a way that, if possible, there is no “no” for the children, there must be a “yes” for everything. The architecture should convey a positive mood. We have seen above how important the role model function of the educators is for development. Only happy, balanced educators can be positive role models! The architecture creates the shell for the social life of children and educators in which the art of education is lived.

Much of what has been touched on here can also be applied to the design of the outdoor areas. However, this is not the subject of this design.

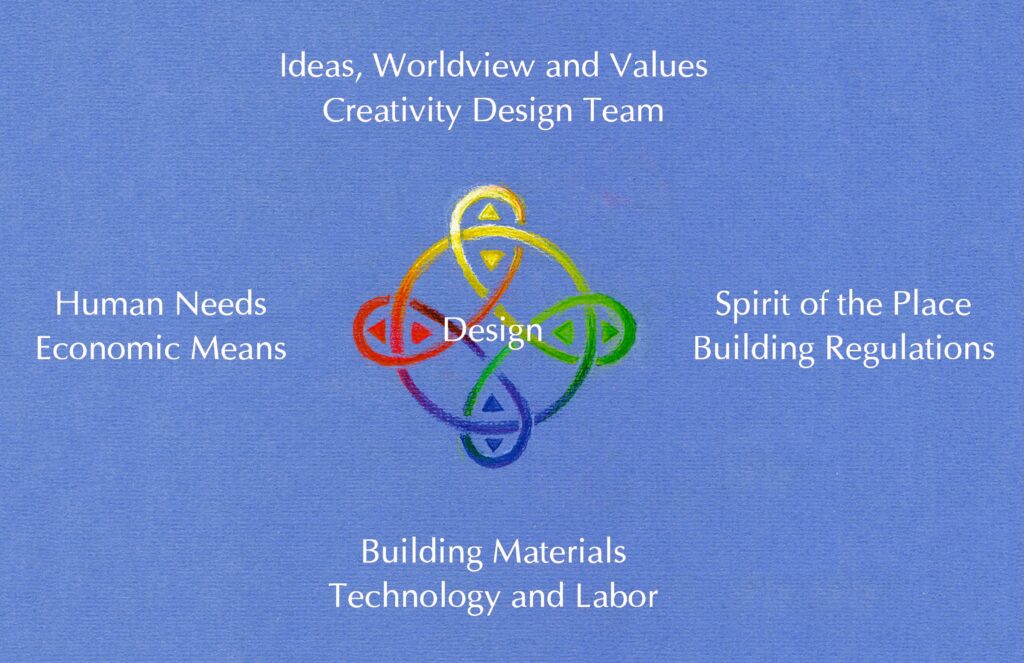

Living Organic Design

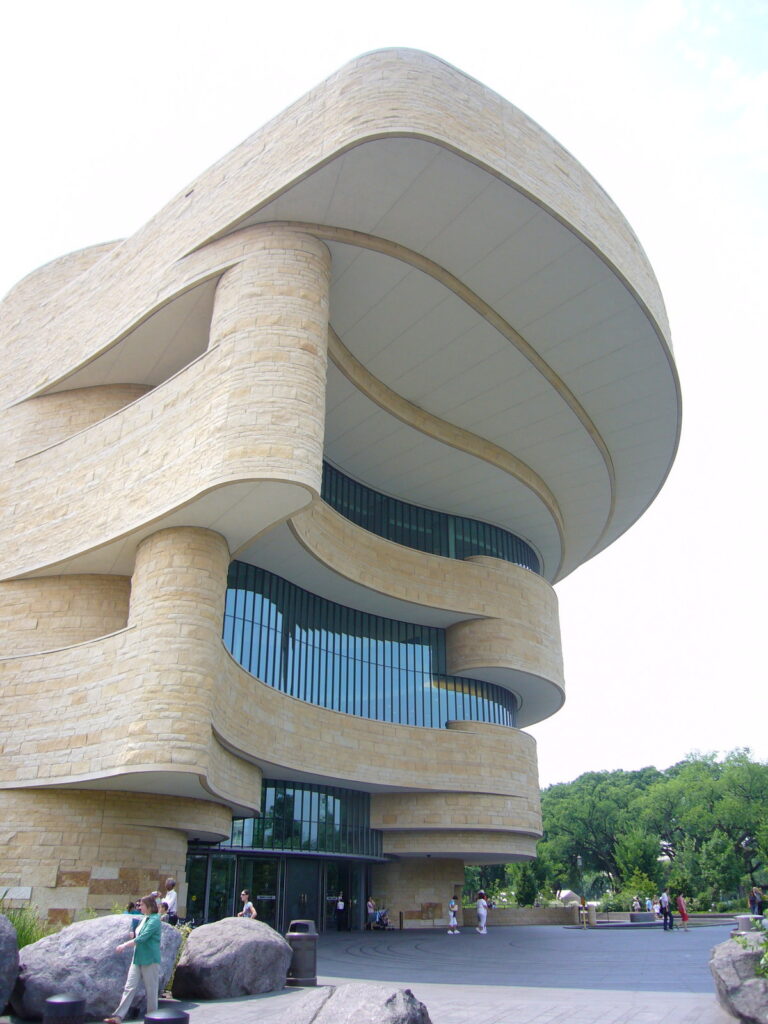

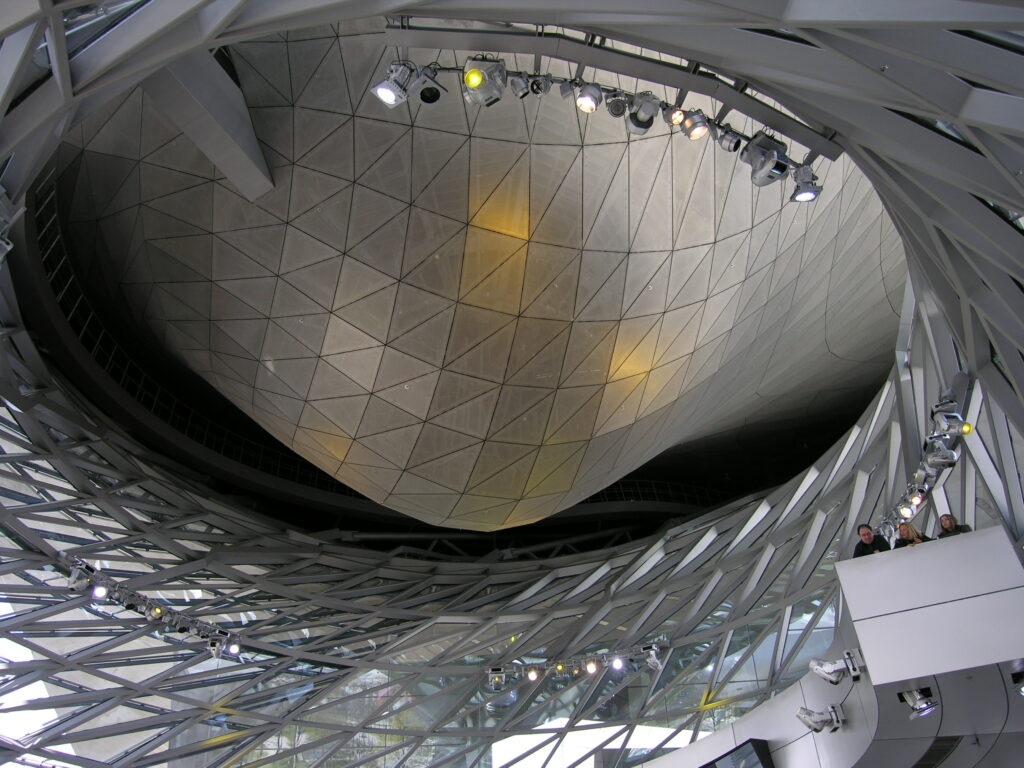

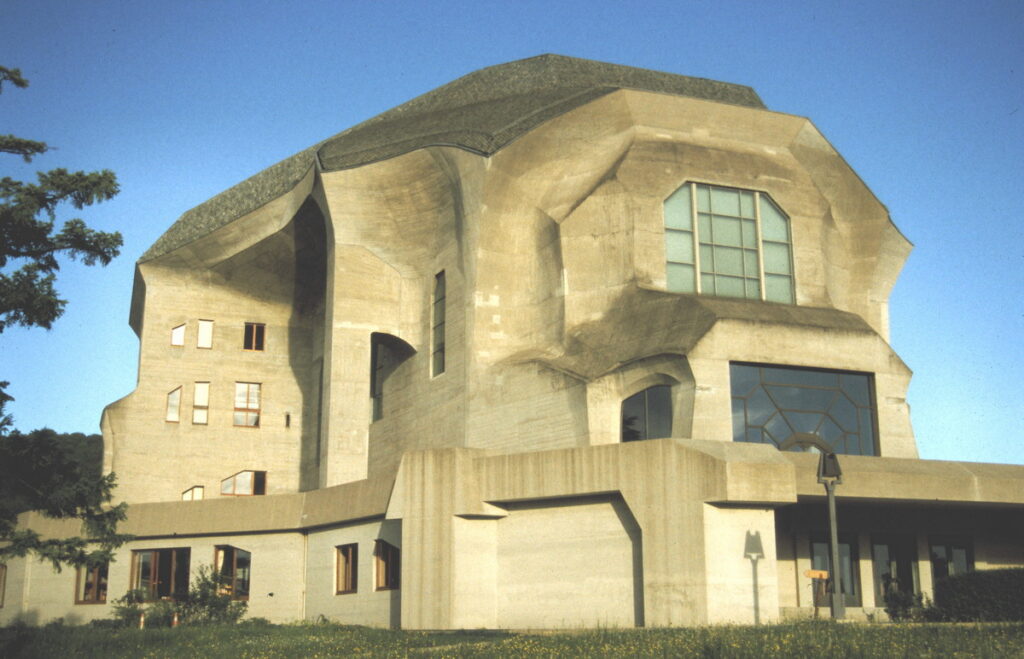

Protection, security and space for development are therefore our starting points for design. Now we have listed many criteria for a day care centre design. The architect’s art is now to bring all these requirements with the realities on site, budget, building site, legal requirements etc. into a shape, a shape that does justice to the task of the day care centre. This must be done by an artistic impulse of the architect. In addition to fulfilling the listed criteria for enlivening sensory perception, something artistic, spiritual must also resonate through the design. Thus, as in the development of children, the above-mentioned points of view must change in a metamorphosis, just as in child development the forces and design impulses are constantly in metamorphosis and cause the life forces to vibrate. Through flowing forms in the floor plan, the life forces become an impulse on the movements through and in the building.

The development of the vertical and the animation through curves are important formal approaches to architectural design. Thus, vertical elements are to be emphasised in architecture, in façade articulation, entrance elements, window format, but also in furniture and fixtures. Through double-curved designs of ceilings and roofs, ethereal, living forms, which we also see in nature, come to life and transform and enliven architecture consisting of solid material. Through such a roof design, for example, protecting, which serves as an approach to pedagogy, can also become visible in the architecture. In this way, the child experiences the bodily formative forces at work in the architecture. The living organic design impulse can make a significant contribution to mastering this task, a spirit-filled design.

Today, it should be a matter of course that the choice of building materials, also with regards to future generations, should largely correspond to ecological, biological and sustainable aspects. However, these aspects must not be formative, but must serve the form that develops from the task.

Search for the Future Being

This article is intended to provide suggestions for individual design approaches. The framework conditions and requirements of the building tasks are far too different to be summarised in design rules or recipes. However, an awareness of the children’s needs and developmental aspects is a prerequisite for the success of the building task.

With this in mind, educators, parents, architects and all those involved must work together to move the building task forward and develop the individual criteria. Through this joint effort, forces will develop that will make it possible to experience the essence of the future as a spiritual impulse. In the creative process of the design, this essence can then show itself as an individual form. The children need openness so that they can develop the forces for their future. In order to do justice to this task, we must also design the architecture from these future forces.

This article was published in “M+A”, 85-86, 2016

All pictures by Martin Riker