Tasks of contemporary organic design

Changes in architecture and in society

For many decades, from the time of its emergence, organic architecture was an antithesis to the prevailing functionalism and the materialistic-scientific thinking associated with it. The differences between the two streams were also clearly recognisable on a formal level, in fact so recognisable that many – especially lay people – mainly distinguished the external features, often without knowing what the difference in content was. For this reason, organic architecture was and still is mistakenly seen by many as an outward style rather than an approach. Even some organic-minded architects have more or less consciously fallen into this mood and have made little effort to deepen the intentions and backgrounds, sometimes only imitating certain formal solutions of the masters. Already with postmodernism, however, the situation has fundamentally changed. The search for more humane, lively and healthy solutions has led several architects, in different ways, to incorporating aspects of the organic approach into their own working methods. Topics that were and are taboo for the functionalists, such as the appearance of the living (in Rudolf Steiner’s words) or individual expression in buildings, can today be more prominent in the work of star architects who do not see themselves as being „organic“ – such as Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Norman Foster and others – than in the work of the organic designers. From the nineties onwards, one can observe a strong, general tendency towards the creation of organism-like buildings. This phenomenon has raised a strong question of self-understanding among organic architects, a question that, in my opinion, has not yet received a clear answer.

In parallel with the aforementioned tendency, however, one can perceive, after the end of postmodernism, a new powerful minimalist and conceptual wave in world architecture, which is certainly in absolute majority on the plan of the numbers of realised buildings.

On the cultural and social level, one finds a similar situation: on the one hand, growing spiritual currents that reach into mass culture (see films such as „Cloud Atlas“ on the theme of reincarnation or entire series of Buddhist-inspired films), and on the other hand, the ever-increasing prevalence of material values and the materialistic way of thinking in art, science and everyday life.

It is not meant that the tendencies in society find a direct and clear expression in architecture. What is common is the appearance of a strong polarisation both in society and in architecture, so that today we can no longer talk about a mainstream (like functionalism in the past) and a small niche that is little noticed by the public (like organic architecture at that time), but about a struggle between comparably strong impulses that take hold of the whole of society.

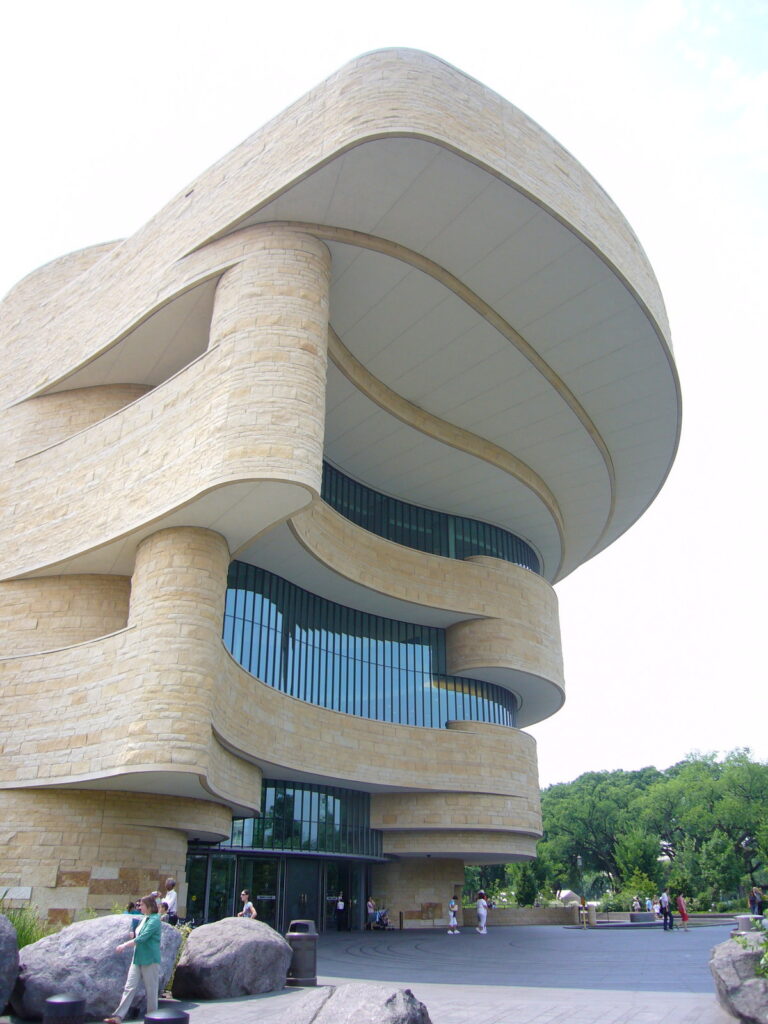

In organic architecture, too, one can see comparable processes in the last 20 years, with the emergence of a fairly widespread “organic minimalism” – partly also due to economic and regulatory conditions – on the one hand, and the interest, sometimes with public success – as in the case of Gregory Burgess, Javier Senosain, Douglas Cardinal, Santiago Calatrava – for distinct and even intensified, formally recognisable organic solutions on the other. It is also worth noting that even the term “organic architecture” has experienced an increasingly broad resonance and application.

Needs behind the time phenomena

The situation described poses various challenges for organic architects.

The interest in many aspects of organic design and the adoption of its approaches in several examples of contemporary architecture speak about a partly conscious, partly unconscious urge in a certain number of our contemporaries. This urge includes, synthesizing, the experience of spiritual and essential qualities, the search for a meaningful relationship between buildings and their surroundings, the creation of a space that is individually designed according to the function of the building and supports both the soul life and the life forces, to name only the most striking points. Today, these aspects appear sometimes together, sometimes separatedly, in the case of clients who are not explicitly looking for an organic design for ideological reasons. I could name several cases from my own experience where people who have no design or anthroposophical background, after encountering examples of organic architecture, recognise them as the expression of their deep-seated desires. What often amazes me in this context is people’s ability to experience and describe the qualities of architecture. There are a many clients who are amazingly good at observing the effect buildings have on them. This characteristic, which is widespread today and which I believe is connected with the general development of humanity, demands of architects a corresponding awareness and the ability to respond to the specific, exterior and inner needs of each individual, and to connect them with the general needs of people today, because every building, even if planned for a specific client, always has a public side and is a part of the urban organism. The perception of the spiritual-essential in architecture, for example, is one of the most important aspects that can satisfy the modern need for the development of individuality. This is the reason why it appears more and more often, even intuitively or unconsciously, outside the organic movement. Similar things can be said with regard to qualities such as the dynamic, the appearance of the living, the transformation of form (if not directly metamorphosis), the experience of polarities and many other things. All these aspects can be traced back to the need for spiritual development of the human being, because they help to form the inner abilities that are necessary for a conscious perception of the spiritual.

The need to develop new abilities

If one wants to meet the needs mentioned above as an architect, one must oneself develop a sense for the qualities and processes described. This was already the case in the beginnings of organic design, and one can see how its pioneers tried in various ways to immerse themselves in the spiritual content of the world. Today, however, this call is even stronger, because the search for spiritual knowledge and even the development of supersensible perceptive abilities – as already indicated earlier – are present in ever broader layers of our society. The tendency, which is often also found among architect-anthroposophists, not to underline or not to mention at all in public the satisfaction of spiritual needs through organic design – perhaps because of the fear of not being understood or accepted – leads to an incomplete and thus unconvincing picture of the aims of organic architecture. For the purpose of developing a contemporary organic approach, it is first and foremost necessary to reconsider its tasks in the light of the times. If one does this, one also easily comes to the realisation that the endeavour to fulfil such tasks depends on the designer’s ability to delve into the deeper layers of reality, which are connected with life, soul and spirit forces. This concerns, for example, the understanding of the clients in their soul constitution and in their destiny and development potential, the understanding of the place with its life forces and spiritual beings, the understanding of the function of the building not only in its physical aspects, the understanding of the time situation and of the cultural environment in which the project will be embedded and much more.

It is precisely in this intention to perceive the world and the building task with all its facets and conditions on the various levels, from the physical to the spiritual, that I think the main difference lies, between organic and especially anthroposophically-inspired architecture and other approaches, which however sometimes also, mainly unconsciously, reach similar results.

In addition to the perceptual abilities that everyone carries in one’s own constitution, new ones can be developed through practice and with the help of experience. This is a large part of the work of those who want to design organically. This does not mean that organic design is not possible without supersensible perceptions, though. Thinking itself is already a supersensible activity, and the question is to what extent one can bring it to life in order to come to the perception of spiritual connections. Something similar can be said about feeling, which – through liberation from emotions and subjectivity – can also become an instrument of perception. At every stage of personal development, the architect can strive to experience as best he can the supersensible aspects of the building task. It is important to understand that humanity is still at the beginning of developing new perceptual abilities, but that it is therefore important to strive for this development. The same is required in all fields: in medicine, in pedagogy, in agriculture, etc.

The topic of developing perceptual skills is particularly relevant in the context of the theme of positive contemporary design, because this is only possible through a genuine and conscious experience of the changing spirit of the time. Imitation or, at best, re-creation based on the work of the pioneers of the organic movement, who had a clear perception of the necessities of their times, could lead to results corresponding to the spirit of the time as long as it had not changed too much. Today, contemporary design based on older examples is no longer possible; it requires independent and well-founded insights.

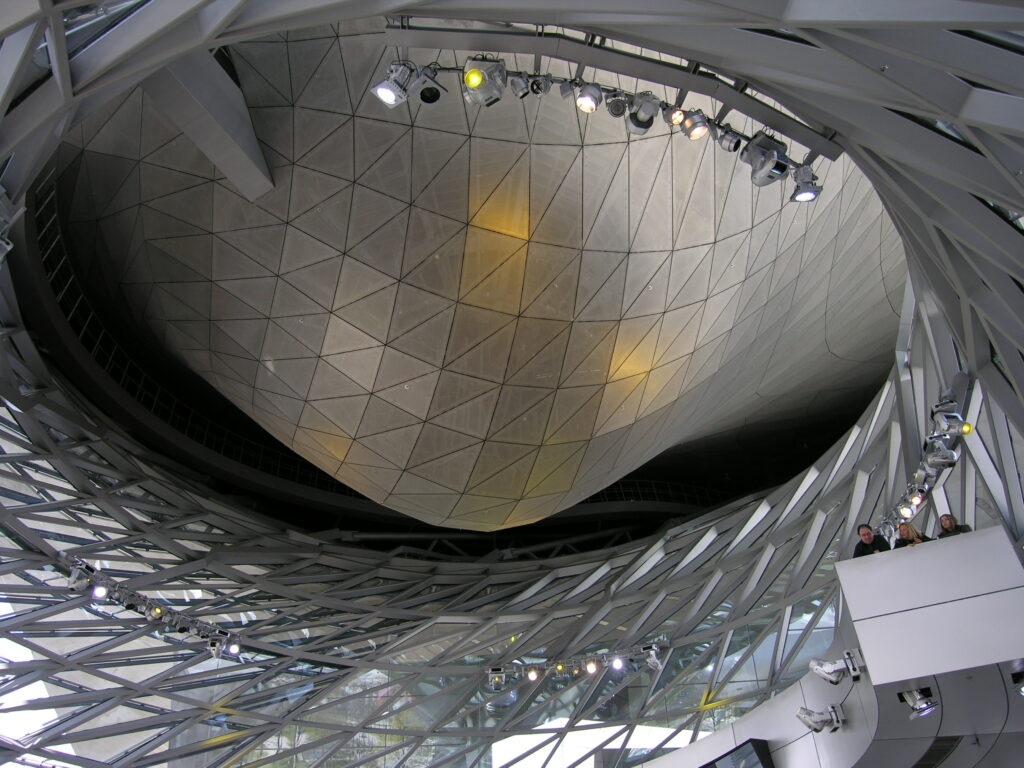

The appearing of being-like qualities (in German „Wesenhaftes“; expression of an individual being) in architecture

One example of this kind of observation – in addition to the tendency towards the appearance of organisms in contemporary architecture mentioned at the beginning – is the emergence of being-like qualities in the interior of buildings. Very striking in this sense is the drop-like ceiling of the hyperboloid part of the BMW Erlebniswelt in Munich by Coop-Himmelb(l)au. Looking at it, one can have the impression that an alien, mysterious being is descending into the space. You get a comparable effect in Frank Gehry’s DZ Bank in Berlin, where a wild figure appears in the courtyard of a fairly conventional building. I believe that such solutions are connected with the increasingly frequent occurrence of supernatural experiences in the consciousness (the interior) of people today and with the longing for them. One can come to this insight with a certain degree of certainty if one looks at the examples mentioned in connection with other phenomena in culture, e.g. films such as “Matrix” or “The Lord of the Rings”. An example of organic design where an attempt is made to connect to this need is, in my opinion, the festivel hall of the Rudolf Steiner School in Salzburg by Jens Peters. In the middle of the lazured undulated ceiling there is a translucent oval that lets in light and that can be perceived as an immaterial apparition in the flood of colours. The big difference with the BMW building is that the brightness of the oval and its embedding in the lazure have more of a friendly and joyful quality, in contrast to the armour-like, wormy and dark character of the drop of Coop-Himmelb(l)au. Thus, a similar approach gives different results depending on what mood of being the designer has connected with. This does not mean any judgement of the different solutions given the different contexts.

Transparency in the interiors

Another example of the changing spirit of time can be the growing transparency within buildings and the possibility of looking through different layers of space simultaneously. The Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart by UN-Studio – like other projects by Ben van Berkel – is designed according to these principles. From each loop of the three-leaf ramp, one gains ever new insights into the other opposite loops through the central triangular space. At the edge of the ramp, at the outermost points, vertical visual connections with the lower levels also open up through glazing. The transparency and visual penetration of space can lead to an experience of the possibility of inner looking and the penetration of different layers of the soul and spirit, which certainly corresponds to a growing need – just think of the development and spread of psychology and psychoanalysis – of the present day. First attempts in this direction in the organic field can be found in the 60s – 70s in the work of Giovanni Michelucci, most strongly in the church of Borgomaggiore (Republic of San Marino), and of Hans Scharoun, especially the foyer of the Berlin Philarmonic Hall. A closer example in time that addresses the visual penetration of spaces is the Weleda administration building in Schwäbisch-Gmünd by the BPR office in Stuttgart. Here, too, one can look from the upper floor through glazing onto the atriums below, which connect several floors vertically, and through another glazing into the open air and onto opposite parts of the building. One can even see the interior behind the glass façade of the conference hall. Thus the view deepens through four layers of space and three glazings, from the inside to the outside into the open air and then back inside again.

Satisfying soul and spiritual needs

The special nature of organic architecture’s approach to the tendencies of the time should again lie in the deepening of its spiritual foundations and in the attempt to grasp and unfold the developmental aspects of such tendencies. This makes it possible not only to passively go along with the general trends, but sometimes to turn them in new directions or to balance out one-sidedness.

An example of this can be seen in the possible attitudes towards the resurgence of minimalism and “objectivity”, which in recent years has been largely related to issues of energy efficiency and economy of means. This has led to the emergence of a largely soulless architecture and, as mentioned at the beginning of the article, has greatly influenced the organic design of recent decades. It repeats – under different conditions – the process that led to the spread of rationalism partly for economic reasons. In this case, the task of the organic designer can be to show how one can create buildings – with consideration for the new demands – that satisfy the soul and spiritual needs of people. Even Rudolf Steiner was already concerned with this question when he designed the Schuurman House and the Transformer House in Dornach. With Frank Lloyd Wright one can also find this concern – especially in the Usonian Houses. The work of Erik Asmussen and the later designs of Winfried Reindl were the first attempts in the anthroposophical field to find a balance between organicism and minimalism.

However, I would not think that this direction is the only possible one for our time. The examination of the reduction of means and the language of form is one pole of contemporary architecture. On the other hand, more and more complicated and expressive, sometimes wild designs are being created today. This belongs to our time just as much as reduction, and organic architects can also deal with this in order to combine the expressive power, which was already noticeable in its most extreme manifestation at the beginning of the 20th century with Hermann Finsterlin, and which – thanks to technical progress – can be even realised today, with an awareness of human needs and of the spiritual in the world. The projects of Douglas Cardinal and Gregory Burgess are examples of this possibility, as they allow an expressive design to emerge from the function and context of the building.

These brief references to features of the period are only small examples to illustrate the approach outlined. I am convinced that an important task of organic architects today is to delve more and more into understanding the developments of society and to engage in a kind of exploratory conversation with each other on the subject, in order to complement the different points of view and perceptions. This can form a basis in terms of content and ideas for a joint effort in the modern world.

Published in M+A 99-100, 1/2019