Rencontre "L'intention et l'inspiration dans le processus de conception" en Alfter

Architects and students from different countries met in May of this year in a workshop on « Intention and Inspiration in the Design Process » at the Alanus University in Alfter near Bonn. The cooperation of the Section for Visual Arts at the Goetheanum, of the IFMA and of the Alanus University, aimed to make it easier for students to participate and to be an active part in the conversation. We, Neja Häbler and Christoph Schmidt, architecture students at the Alanus University, were very pleased to have the opportunity to help in the development and organization of the conference. In the small but multinational group, a lively exchange arose on the conference theme. The daily prelude, led by Willem-Jan Beeren, served the perception training and offered a practical introduction to the topic. Basing on movement exercises, one could feel the personal intentions of the participants, made visible by the way they acted. The contributions by experienced architects as well as students, highlighted personal working methods and sources of inspiration. Besides that, they formed the basis for the subsequent rounds of talks. The different approaches of the speakers showed various aspects and attitudes towards architecture. The controversial discourse about the role of architects and the human contribution in the design process, brought up the question of « space » as a possible theme, which could be taken up in future meetings.

Neja Häbler, Christoph Schmidt (Germany)

In May, at the Alanus University in Alfter, young and adult practicing architects and architecture students interested in Organic Architecture gathered to exchange experiences and deepen the theme of “Intention and inspiration in the design process“. Such occasions are very meaningful to me, as they represent a chance to meet directly people from around the world who are, in their own way, trying to work in a similar direction.This gathering had also the particularity that a couple students from Alanus became an active and a vital part of its organization, which I found pretty inspiring. This active participations of students who, like myself, are curious to learn and experience the theory and practice of architecture through the lens of Rudolf Steiner’s worldview, was a novelty to me. This workshop, that was attended by numerous students alongside architects, was characterized by a joyful and enriching atmosphere full of genuine curiosity and enthusiasm. The will of sharing, a thirst for knowledge, a curiosity that wants to be fulfilled, the desire of finding something meaningful were tangible energies that the meeting brought forth. The balance between generations is something pretty unusual within the niche of Anthroposophical Architecture. This unique environment led at the end of the meeting, after various contributions and practical exercises during the first days, to fundamental questions on the interplay between form and matter, the intrinsic meaning of sustainability and the essential importance of the experience of the architectural space. Future and new gatherings like this are essential to start building a diverse and robust network of young and adult architects who need constant coming together in order to explore new questions and solutions fitting the present time.

Nicolas Gemelli (Italy)

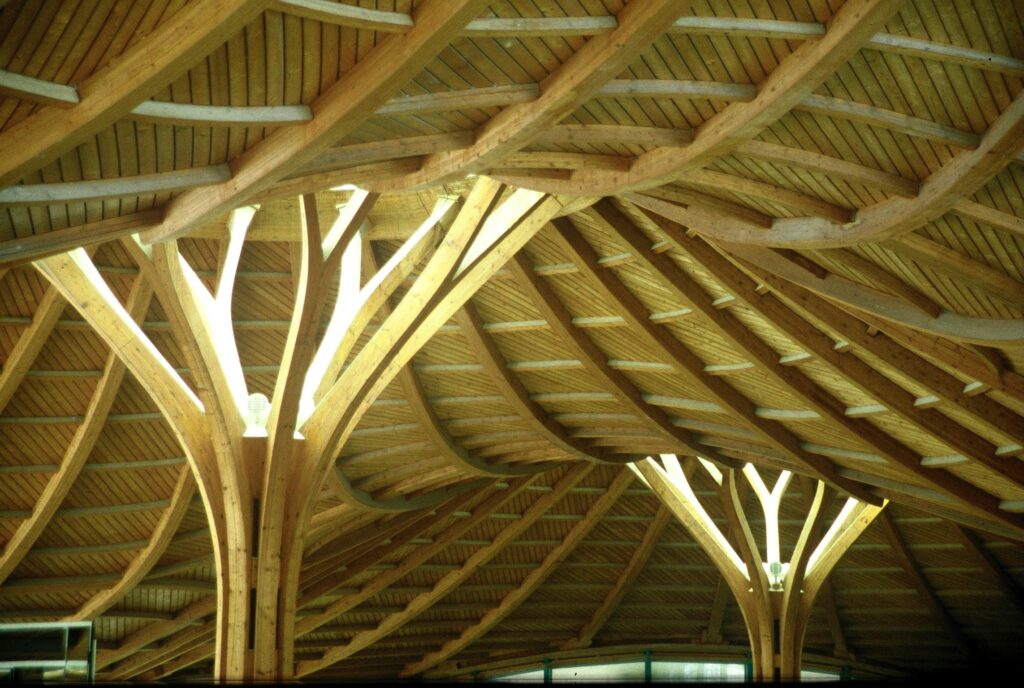

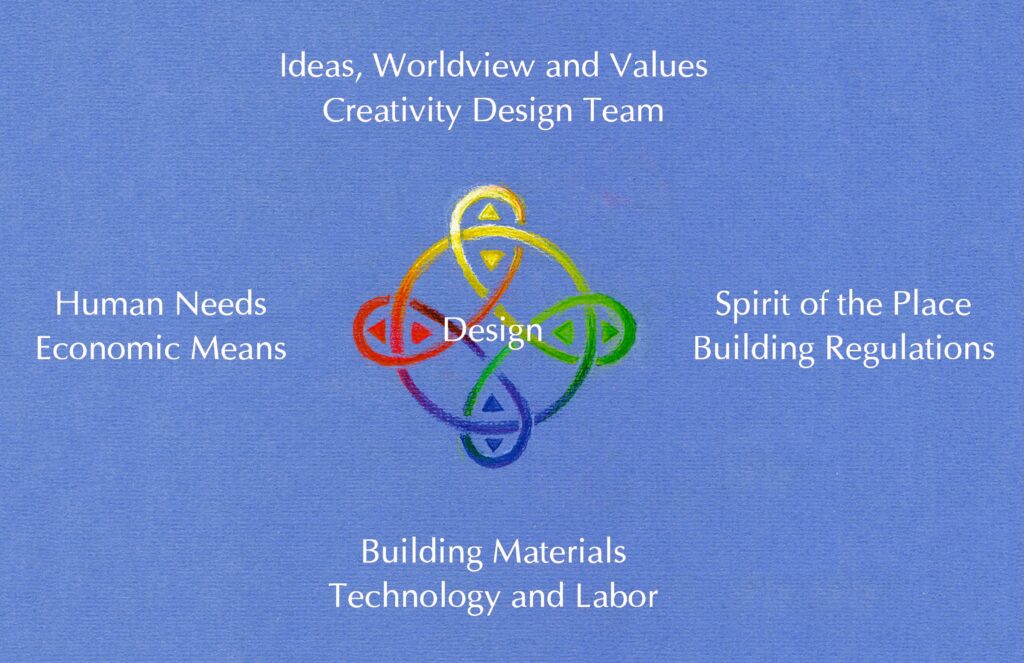

The meeting in Alfter was a first attempt to unfold a conversation between students / young architects and experienced planners, starting from questions asked by young participants to the architecture conference held at the Goetheanum (Dornach, CH) in October 2022. In order to shape the event basing on the wishes of the younger participants, two students of the Alanus University were asked to be part of the preparation group. Till the beginning of the gathering, it was not clear how many people would attend, also because of the late publication of the program. In the end an interesting group of about 20 – mainly students from Alfter and students and young architects from Italy, Mexico and Belgium – came together. I very much appreciated the interest and the engagement of the participants, which led to lively discussions, stimulated by the contributions of Gregory Burgess (Australia), Ragnhlid Klußmann and Martin Riker (Germany), who gave a deep insight into their design approaches and into the way they develop intentions and come to inspirations. It was also exciting to see on Saturday evening the projects of some of the students, both from Germany and Italy, hearing how they come to solutions, and to notice the differences in their attitudes and motivations. The conversations which followed the project presentations were very stimulating and represented for my feeling a culmination of the event. Also the two workshops, one in English and one in German, were an occasion of experiencing how different generations of architects address one and the same task, and of exchanging and comparing various approaches. In the final conversation several questions and themes arose and became object of discussion, for instance the relationship between art and architecture, the choice between strongly individualized design and flexibility, how to understand sustainability in the context of organic design, how to come to a real experience of the quality of space and architecture, to which extent the design of a space affects the social life within itself. It was encouraging for me to see how interested the young participants were in these issues. At the same time I had the impression that many of the aspects we touched are still unexplored for them and that it would be helpful to deepen them in future meetings. In general, I am very thankful for this occasion of getting to know more closely the new students of the Alanus University, who are certainly different from the ones I teach in Ukraine and Italy. I hope this was the beginning of an exchange which will continue in the next years.

Luigi Fiumara (Italy – Ukraine)

A most enriching part of this workshop was to come in contact and exchange ideas with a generation of future architects, and at the same time to exchange and hear from experienced professionals. As I seat between these two poles, I reflect upon the themes brought about and I can say that it all comes down to culture, sense of place and natural environment when it comes to architectural intentions. Each culture, place and environment live with its own questions and its own particular answers that can only be dealt with from within-out. Perhaps if such kind of workshops could be done in different locations, the processes would enrich and diversify the outcomes, along with mixing the work teams not just by language but also a mix of age and gender etc.. The question of inspiration is of the outmost importance in an age where AI can give all the answers making the architects imagination handicap and forgotten, though I am convinced that algorithms will never replace the human capacity of Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition. The theme of inspiration still needs a whole lot of investigation, imagination, and application at a personal and community level within architecture, to start to comprehend it and thus allow a complete flow of the Will of the Spirit to be active in us as we and specially our creative thoughts become the future architecture.

Cecilia Ramirez Corzo (Mexico-Japan)